If you’re a regular reader of Expat Living, you’ll know that we enjoy following the travel adventures of the HER Planet Earth team as they explore some of the world’s farflung corners. This time, they journey across Greenland – by bicycle!

There’s no doubt that traversing the full length of Greenland’s Arctic Circle Trail at the heart of winter on a bike will stand as one of the most extraordinary and unique experiences of my life. The journey saw the HER Planet Earth team push our limits to the brink of exhaustion on multiple occasions in extreme conditions and temperatures, across one of the most awe-inspiring and stunningly beautiful places I’ve witnessed.

The goal of this pioneering expedition was to raise awareness and funds (a team total of $50,000) for underprivileged women affected by climate change in Asia. Why Greenland? Because it’s one of the last final frontiers. Eighty percent covered in ice, its glaciers are contributing to a rise in the global sea level faster than was previously believed. As this accelerates, many coastal cities will be affected – and Asian cities will be hit much harder than others given their population, economic activity and landmass. The processes that control sea-level rise are amplified in Asia. As a result, about four out of every five people impacted by sea-level rise by 2050 will live in East or Southeast Asia.

Initial impressions

Stepping off the plane in Kangerlussuaq, a small town in western Greenland with a population of a few hundred people, feels like we’ve landed at the edge of one of humanity’s last settlements. The minus 33°C temperature hits me in the face instantly. Dry air fills my nostrils and lungs; it’s as if I’m suddenly inhaling ice particles that freeze me from the inside out.

Waiting for us at the tiny airport terminal is a giant of a man, Bo Lings. Standing in front of us with a warm and welcoming smile, he is quite literally the largest man I’ve ever shaken hands with! Immediately, he inspires a deep sense of confidence and calm in our team. We understand we’re in very good hands.

After a short drive from the airport, we check into our shelter accommodation, which looks more like an army barracks than a hotel. We change excitedly into our biking clothes. This is the moment we’ve all been waiting for. We pull on layer upon layer: thermals, fleeces, soft shell jackets, windproof jackets, balaclavas, inner gloves, outer gloves, woollen socks, insulated boots, helmets and goggles. The list is interminable, yet each piece has its precise function, necessary to safeguard us from the Arctic conditions.

We collect our fatbikes – off-road bikes with oversized tyres that are designed for low ground pressure to allow riding on soft, unstable terrain. We adjust our saddles and install our “pogies” – jumbo mittens that fit over the handlebars for added warmth. By the time we arrive by bus at the foot of the Russell Glacier, the starting point of our 200km journey, it’s already 4pm and a sobering minus 35 degrees.

Setting off

The glacier is magnificent, a sharp contrast to the surrounding land and icescapes. With an impressive, jagged ice wall that reaches 60 metres in parts, it stands against the deep blue sky like a white giant with turquoise cracks and crevasses.

“These structures can calve and break at any time,” says Bo. “So it’s important we remain at a safe distance.”

I take in the view, but my mind is on the biking. We have 26km to ride back to our shelter for the night. Should be a piece of cake, right? Wrong. From the first few pedal strokes, I realise it’s going to be a real struggle. The snow around the glacier is powdery, thick and slippery, so we skid, swerve and fall multiple times like clumsy circus clowns, before finding our footing. It’s not a good start.

The cold is quite daunting this late in the day, and as the wind picks up, minus 35 feels more like minus 40 or worse. When not pedalling, we really feel it in our bones and extremities. Luckily, we soon hit harder snow on the dirt road; it’s much easier to pedal on. We finally pick up speed and settle into a good pace – and with that comes more body heat.

That first day, we cycle up and down over the rolling hills for what seems like an eternity. Soon, the sun sets and the temperature plummets. The team is quite spread out. Everyone is finding their own pace, getting used to the snow, the bikes and taking it all in. Thankfully, despite the growing darkness, there is a beautiful full moon welcoming us to Greenland, and illuminating our path. Four long hours later, just before 8pm, we reach our shelter. As we take off our goggles, ice forms on our eyelashes and around our balaclavas as our breath freezes in cold and wind.

We’re spent. We thought this would be a warm-up day; instead, with jetlag and no lunch, it was intense and draining. Many of us have been up since 4am Copenhagen time, which is four hours ahead of Greenland; but really, most of us are still on Asia time, which is eleven hours ahead.

Tomorrow, we have 60km on the itinerary – and no road this time, just a path in the snow. That evening, after a hearty meal, we crash into our beds exhausted, wondering with apprehension what tomorrow will bring.

The journey continues

The next day is a killer – tougher than we ever imagined – but we survive it … just! We cycle our hearts out to the brink of exhaustion and reach our hut in complete darkness. After ten hours in the cold with just our thoughts for company, we advance across this interminable white desert and arrive shattered, cold and wet.

Every bone and muscle hurts. This was the day that never ended. We continually longed for Bo’s support vehicle to appear in the horizon, with hot tea or soup, and words of encouragement. During those precious breaks, it was important never to stop for long, because, despite the added down jacket we quickly threw on, we got too cold, too fast.

That night at the hut, we sleep like the dead.

The next morning at dawn, we wake to the howling of dogs outside our cabin. They arrived the night before at the helm of a sled piloted by a local Inuit couple. Inuit are the indigenous people of Greenland; they make up 90 percent of the population, having originally migrated from Alaska through Northern Canada.

After breakfast, we get on our bikes and start across a vast frozen lake. Our expedition guide Paul, an ex-British military officer who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, reminds us: “Be bold, start cold! Not too many layers, ladies!” Stepping out from the warmth of the hut into the glacial morning air, it’s not easy advice to follow.

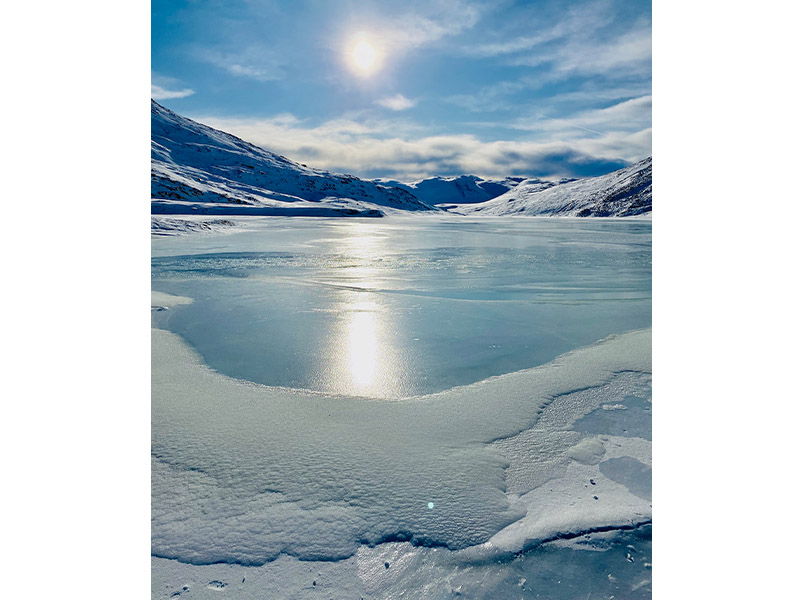

We cycle in silence for a couple of hours across the lake. The clouds are low and visibility poor. We focus on the person’s tracks ahead of us, and in those instances of deep concentration, it’s easy to think of absolutely nothing, just simply be present in the moment. Then, as we reach the other side of the lake, we begin to climb towards a mountain pass, sometimes getting off to push in the steepest parts.

Mountains and more

Getting up mountain passes while pushing a 13kg fatbike, carrying a 6kg pack and breathing through a balaclava is an exhausting job. To encourage myself when I get dog-tired, I count 50 paces in my head, then stop to catch my breath. Once on top, though, we’re always rewarded with breathtaking views. The valleys and frozen lakes below are spectacular; we gaze in awe and ponder our own insignificance.

Subsequently, from these heights, the downhills are formidable, a much-deserved reward after the long, hard slogs. Descending a snowy trail at full speed on a fatbike, with towering mountains all around in the remote wilderness of Greenland, makes me feel more alive than I’ve felt in a long time.

The next four days vary in distance from 22km to 33km. Some days are harder than others, but after the 60km leg, we feel we can tackle anything. The journey unfolds and we make good progress. Each day, we push our limits even further as we battle the extreme conditions.

We ride on all types of terrain, from hard-packed and powdery snow, to ice, mud and rock. The days on the trail are long and tiring, with no shelter from the cold and wind for up to eight hours. Despite the gruelling conditions, the esprit de corps is strong. We encourage each other, make each other laugh, a lot – it makes all the difference. The faster ones learn to slow down and wait for those who are catching up. The team is tight, and gradually becomes a high-functioning unit. We discipline ourselves to stay close together despite the different biking paces, because if someone gets lost, hurt and left behind, they could freeze to death or die of hypothermia within hours.

Final leg

The last day seems like one of the hardest. We’re so close to our goal yet still so far, and even though we’re looking forward to a warm bed and a hot shower, there is sadness in our hearts too – the journey has come to an end so soon.

The snow has changed; it’s softer and more slippery as we approach the coast. The sky is grey, and visibility limited again. We see nothing and need to stay focused. There is a very steep ascent to start, and the first few hours are difficult and slow. The descent after that is tricky and we experience many falls and wipe-outs, but we’re determined to be cautious so as not to break any bones so close to our finish line.

By mid-afternoon, we finally ride into the coastal fishing town of Sisimiut. With a population of 5,500 people, it’s the second largest city in Greenland. Suddenly, we’re back to civilisation. It’s a strange feeling after days in the vast white emptiness of the Arctic Trail. There are cars, snowmobiles, dog sleds, and people walking in the snowy streets, staring at our convoy of bikes.

We arrive at Bo’s warehouse and suddenly realise… that’s it.

We did it!

Reflecting on the experience

We get off our bikes and start to embrace, overwhelmed with emotion, perhaps even relief. It’s been one of our most difficult challenges. We were travelling as a team, yet most of the time, we were alone in our thoughts, behind our goggles and our balaclavas.

The sense of happiness and achievement is palpable, and our eyes fill with tears of joy. We are the first all-female team to fatbike the frozen lands of the Arctic, connecting the Russell Glacier with the western coast of the world’s biggest island, Greenland. Yet it’s the experience as a team that bonds us more than the achievement itself.

There’s no doubt that Greenland’s savage beauty has changed us forever. This wild land has a fragility that is calling us to wake up to a new world reality. We’re all connected to it somehow and our destiny seems interlinked to its survival. Nations, like individuals, come to light in times of crisis. Indeed, what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic, but will surely shape humanity’s future and survival – possibly sooner than we think. The question is whether each of us will do our part to safeguard our planet and its most vulnerable, or simply be a bystander.

See more in our Travel section