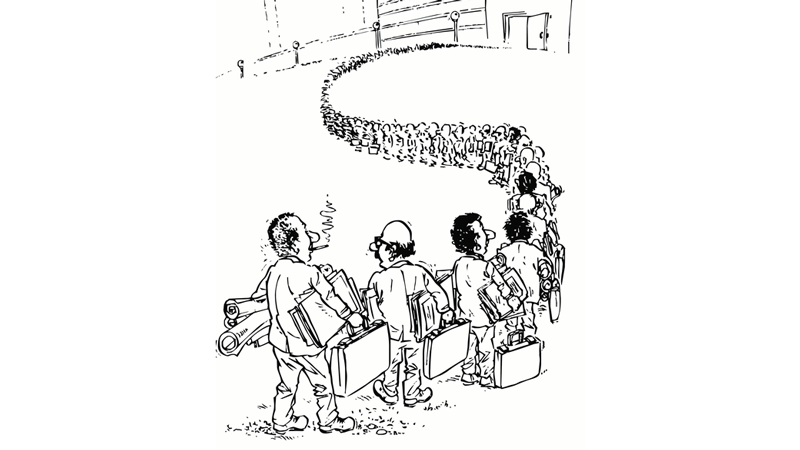

I’ve been around and about. I’ve lived on three continents; I’ve worked in and visited over 40 countries. I am British, and frankly I considered myself an internationally superior queuer. That is, until I moved to Hong Kong.

It’s a rite of passage for British children to become expert queuers. There are unwritten rules about what to do when someone strays a little too far from the line or when there’s a collective need to snake round to avoid obstructing others. Over time, the rules have evolved to adapt to modern living. Cash machines have their own special etiquette: keep far enough away that you can’t read the pin but close enough to make it clear you’re next.

The Brits feel nothing but disdain for people who fail to see the importance of good manners whilst queuing. But in Hong Kong the queuing etiquette is born of something else. It’s born of a fear of disorder. Whilst the Brits fear a denigration of manners, Hong Kong locals fear chaos. A chaos that would engulf and unravel this small highly populated territory.

As a result, the queuing here takes on different characteristics from home. There’s no talking, absolutely no eye contact. This is queuing with a mission and a clear focus.

Taxis queue for petrol, you have to queue for a slot to give birth, people queue for years for social housing, cars queue to escape the island by tunnel. There are queues for just about everything. And if you want to jump the queue, well that is the reserve of the uber-wealthy.

Some things even have multiple queues. Get in the wrong queue for a lift and you could find yourself stranded in the wrong half of a building with no choice but to descend to ground and re-queue.

There is a compulsion factor to the queues here that I have never experienced at home. In particular I refer to a mysterious queue halfway up the outdoor escalator in Central. Every time I pass it, people are queuing to do something with their Octopus card. Then they just walk on. I’ve no idea why they queue but I feel compelled to join. I want to be part of the mission.

Not only are the queues superlative in their formation but there’s an arrogance about how well they do it that, as a Brit, I can relate to and frankly admire. The opinion of Chinese mainlanders’ ability (or inability) to queue is so scornful it has the potential to escalate to the level of an international diplomatic incident.

This is where the locals have developed their own unwritten and steadfast rules. You must follow the designated exit out of the car park. Often car parks are like passport control in the early hours of a weekday morning; nobody in the queue and yet you’re still made to walk a mile back and forth along a demarcated pathway. Hong Kong’s car parks follow the same principle. You’re forced to drive round and round for an age when you could just nip across some empty spaces and be free. Yet nobody, bar a few expats, will dare to stray from the long queue with no one in it.

On the rare occasion I see a local breaking the car park queue rules, I celebrate. I admire their queue rebelliousness. I accept that I am no longer an internationally superior queuer. We Brits are no longer internationally superior at anything.

Like this? See more in our Living in Hong Kong section

Hiring a helper: 10 questions to ask

Fun things to do in Hong Kong